Quickstart

Hi there! Welcome to the official Remainder documentation/tutorial. For the code reference, see this site. Note that Remainder is specifically a GKR/Hyrax prover and that this tutorial assumes familiarity with basic concepts in zero-knowledge and interactive proofs. For a gentler introduction to the basics behind verifiable computation, interactive proofs, and zero-knowledge, see Chapter 1 of Justin Thaler's wonderful manuscript.

The documentation is split into four primary parts:

- The first is an intuitive introduction to the "GKR" interactive proof scheme for layered circuits. The name "GKR" refers to Goldwasser, Kalai, and Rothblum, the co-authors of the paper which first introduced the notion of proving the correctness of layered circuits' outputs with respect to their inputs via sumcheck. If you are not familiar with GKR concepts, we strongly recommend you read this section before engaging with either of the next two sections or even the quickstart below.

- The second follows from the first and dives a tad deeper into the specific methodology of layerwise relationships, prover claims, etc. and explains the various concepts behind GKR in a loosely mathematical fashion.

- The third is a guide to Remainder's frontend where we explain how the theoretical concepts described in earlier sections can be used in practice. It contains a lot of examples with runnable Rust code, and it can be studied independently or in conjunction with the second section.

- The final is an introduction to the Hyrax interactive proof protocol, a "wrapper" around the GKR protocol which offers computational zero-knowledge using blinded Pedersen Commitments.

In addition, we provide a concise "how-to" quickstart here. This quickstart covers the basics of using Remainder as a GKR proof system library, including the following:

- Circuit description generation

- Appending inputs to a circuit description

- Proving and verifying

Creating a Layered (GKR) Circuit

See frontend/examples/tutorial.rs for code reference. To run the test yourself, navigate to the Remainder_CE root directory and run the following command:

cargo run --package frontend --example tutorial

To define a layered circuit, we must describe the circuit's inputs, intermediate layers and relationships between them, and output layers. We'll first take a look at the build_circuit() function. The first line is

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let mut builder = CircuitBuilder::<Fr>::new(); }

This creates a new CircuitBuilder instance with native field Fr (BN254's scalar field). The CircuitBuilder is where all circuit components (nodes) will be aggregated and compiled into a full layered circuit.

The next line is

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let lhs_rhs_input_layer = builder.add_input_layer("LHS RHS input layer", LayerVisibility::Committed); let expected_output_input_layer = builder.add_input_layer("Expected output", LayerVisibility::Public); }

This adds two input layers to the circuit (see the Input Layer page for more details). Note that an input layer is one which gets all claims on it bundled together and is treated as a single polynomial (multilinear extension) when the prover decides how to divide the circuit inputs to commit to each one.

In this example we separate the input data into two separate input layers because we want some of them to be committed instead of publicly known. This means that the verifier should only be able to see polynomial commitments to the MLEs on such input layers (see Committed Inputs). Depending on the proving backend used (plain GKR vs. Hyrax), committed layers can act as private layers in the sense that the verfier learns nothing about their contents when verifying a proof (more on that later on).

We then have the following:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let lhs = builder.add_input_shred("LHS", 2, &lhs_rhs_input_layer); let rhs = builder.add_input_shred("RHS", 2, &lhs_rhs_input_layer); let expected_output = builder.add_input_shred("Expected output", 2, &lhs_rhs_input_layer); }

We add three input "shred"s to the circuit, the first two being subsets of the data in the "LHS RHS input layer", and the last one being (the entire) "Expected output" layer. Each "shred" has 2 variables (i.e. has evaluations, and is identified with a unique string, e.g. "RHS"). The difference between an input layer and an input "shred" is that the latter refers to a specific subset of the input layer's data which should be treated as a contiguous chunk to be used as input to a later layer within the circuit.

We begin adding layers to the circuit:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let multiplication_sector = builder.add_sector(lhs * rhs); }

Notice that even though lhs and rhs are input "shred"s from the same input layer, because we added them as separate "shred"s earlier, we can now use them as separate inputs to be element-wise multiplied against one another. In general, input layers are treated as a single entity by the verifier, while input shreds are treated as subsets of input layers which the prover can use as inputs to other layers within the circuit.

This first layer is a "sector", which is the Remainder way of referring to structured layerwise relationships. This simply means that with evaluations in lhs and in rhs, the resulting layer should hold the element-wise product of the evaluations in lhs and those in rhs, i.e. .

We add another layer to the circuit:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let subtraction_sector = builder.add_sector(multiplication_sector - expected_output); builder.set_output(&subtraction_sector); }

This layer is another element-wise operator, but where we element-wise subtract all of the values rather than multiply them. Here, we are semantically subtracting the expected_output from the earlier layer we created which was the element-wise product of the values in lhs and rhs (see this section for more details). The resulting layer should be zero if the two are element-wise equal, and we thus call builder.set_output() on the resulting layer, which tells the circuit builder that this layer's values should be publicly revealed to the verifier (and that no future layer depends on the values).

Finally, we create the layered circuit from its components:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { builder.build().expect("Failed to build circuit") }

This creates a Circuit<Fr> struct which contains the layered circuit description (see GKRCircuitDescription), the mapping between nodes and layers (see CircuitEvalMap), and the state for circuit inputs which have been partially populated already.

Populating Circuit Inputs

First, we instantiate the circuit description which we created above (see the function main()):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let base_circuit = build_circuit(); let mut prover_circuit = base_circuit.clone(); let verifier_circuit = base_circuit.clone(); }

Note that we additionally create prover and verifier "versions" of the circuit. The reason for this is that the prover will want to attach input data to the circuit, whereas the verifier will want to receive those inputs from the proof itself and will not independently attach inputs to the circuit this time around. We additionally note that in general, rather than generating the circuit description once and then cloning for the prover and verifier, we will usually generate the circuit description and serialize it, then distribute the description to both the proving and verifying party. The above emulates this but in code.

The next step to proving the correctness of the output of a GKR circuit is to provide the circuit with all of its inputs (including hints for "verification" rather than "computation" circuits, e.g. the binary decomposition of a value; note that Remainder currently does not have features which assist with computing such "hint" values and these will have to be manually computed outside of the main prove() function). In the case of our example circuit, we have the following:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let lhs_data = vec![1, 2, 3, 4].into(); let rhs_data = vec![5, 6, 7, 8].into(); let expected_output_data = vec![5, 12, 21, 32].into(); }

The vec!s above define the integer values belonging to the input "shreds" which we declared earlier in our circuit description definition (recall that "shreds" are already assigned to input layers). Additionally, since we declared earlier that e.g. let lhs = builder.add_input_shred("LHS", 2, &input_layer);, where the 2 represents the number of variables as the argument of the multilinear extension representing that input "shred", we have values within each input "shred", i.e. 4 evaluations for each of the above.

We ask the circuit to set the above data using our string tags for the input "shred"s (note that we need an exact string match here).

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { prover_circuit.set_input("LHS", lhs_data); prover_circuit.set_input("RHS", rhs_data); prover_circuit.set_input("Expected output", expected_output_data); }

Generating a GKR proof

We next "finalize" the circuit for proving, i.e. check that all declared input "shred"s have data associated to them, combine their data with respect to their declared input layer sources, and set up parameters for polynomial commitments to input layers, e.g. Ligero PCS.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let provable_circuit = prover_circuit .gen_provable_circuit() .expect("Failed to generate provable circuit"); }

Finally, we run the prover using the "runtime-optimized" configuration:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let (proof_config, proof_as_transcript) = prove_circuit_with_runtime_optimized_config::<Fr, PoseidonSponge<Fr>>(&provable_circuit); }

This function returns a ProofConfig and a TranscriptReader<Fr, PoseidonSponge<Fr>>. The former tells the verifier which configuration it should run in to verify the proof, and the latter is a transcript representing the full GKR proof (see Proof/Transcript section for more details).

Verifying the GKR proof

To verify the proof, we first take the circuit description and prepare it for verification:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { let verifiable_circuit = verifier_circuit .gen_verifiable_circuit() .expect("Failed to generate verifiable circuit"); }

Finally, we verify:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { verify_circuit_with_proof_config::<Fr, PoseidonSponge<Fr>>( &verifiable_circuit, &proof_config, proof_as_transcript, ); }

This function uses the provided proof_config and executes the GKR verifier against the verifiable_circuit, i.e. the verifier-ready circuit description. The function crashes if the proof does not verify for any reason, although in this case it should pass.

Congratulations! You have just:

- Created your first layered circuit description,

- Attached data to the circuit input layers,

- Proven the correctness of the circuit outputs against the inputs, and

- Verified the resulting GKR proof!

GKR Background

This section describes the basics of GKR, including necessary notation, mathematical concepts, and arithmetization, as well as a high-level description of how proving and verification works in theory.

Notation Glossary

Note that each of these definitions will be described in further detail in the sections to come, but are aggregated here for convenience.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| A finite field. | |

| Layered arithmetic circuit. | |

| Depth of the circuit . | |

| Layer of the circuit, such that any node on is the result of a computation from nodes in layers and , such that . (Note that the GKR literature conventionally labels its circuit layers backward, from for the input layer to for the output layer for a -layered circuit. We follow this convention in our documentation.) | |

| The value of at node , such that is a label for a node in . We say that has bits. | |

| A function . This is the unique multilinear extension encoding the function | |

| A function: which indicates whether | |

| A function: which indicates whether |

High-level Description

GKR is an interactive protocol which was first introduced by Goldwasser, Kalai, and Rothblum [2008]. It proves the statement that , where is a layered arithmetic circuit, and is the input to the circuit.

At a high-level, it works by reducing the validity of the output of the circuit (typically denoted as layer , , for a circuit with depth ), to the previous layer of computation in the circuit, Eventually, these statements reduce to a claim an evaluation of the input as a polynomial. If the input is encoded as the coefficients of a polynomial , we are left to prove that .

The later sections unpack these reductions, showing how we can reduce the claim that to a polynomial evaluation at a random point.

Why GKR?

GKR has several key advantages when compared with other proof systems:

- Not having to cryptographically commit to the entire "circuit trace":

- In general, proof systems which use e.g. PlonK-ish or R1CS/GR1CS arithmetization require a polynomial commitment to all circuit values.

- The size of this commitment often determines the memory/runtime/proof size/verification time of such systems, as the PCS (rather than the IOP) tends to be the bottleneck re: the aforementioned metrics.

- GKR, on the other hand, does not require a commitment to any "intermediate" values within the circuit, i.e. those which can be computed using addition/multiplication from other values present within the circuit.

- For certain layered circuits (e.g. neural network circuits, where the intermediate activation values "flow" through the model and can be fully computed from the weights and model input), this substantially reduces the number of circuit values which require cryptographic operations (e.g. circuit-friendly hash function, MSM, FFT), reducing the bottleneck which the PCS step normally imposes.

- Natively multilinear IOP which depends almost wholly on sumcheck and other linear, embarrassingly parallel operations -- sumcheck is an extremely fast, field-only primitive which is extremely parallelizable and lends itself to various small field + extension field optimizations, resulting in an extremely fast prover.

- Easy lookup integration with both LogUp and Lasso. The former, in particular, is expressible via a very lovely structured circuit, and is time-optimal within GKR with respect to the number of lookups (linear # of field operations in number of witnesses to be looked up + lookup table size).

Interactive Protocol

In the following sections, we start with some necessary background, such as Multilinear Extensions and the Sumcheck Interactive Protocol. We then move on to use these two primitives in order to build out the GKR protocol, which involves encoding layer-wise relationships within the circuit as sumcheck statements.

Finally, we move on to some protocols used within the Remainder codebase, such as claim aggregation, and detail the differences between what we call "canonic" GKR and "structured" GKR, both of which are implemented in Remainder.

Statement Encoding

The GKR protocol specifically works with statements of the form , where is a layered arithmetic circuit. Define a singular value, , to be the output layer, , and the input values to make up the input layer, .

For any layer, the following invariant holds: if a value is in , then it must be the result of a binary operation involving values in layers such that . It is possible that , but not necessary.

These binary operations are usually referred to as "gates." In the following tutorial we will be focusing on two gates: gates, which are represented by the following function:

and gates:

In other words, if we think of a physical representation of , the binary gates represent the "wires" of the circuit. They show how the values from wires belonging in previous layers of the circuit can be used to compute a value in a future layer (from input to output). In fact, for every value with label in layer such that or for as labels for values in layers .

Example

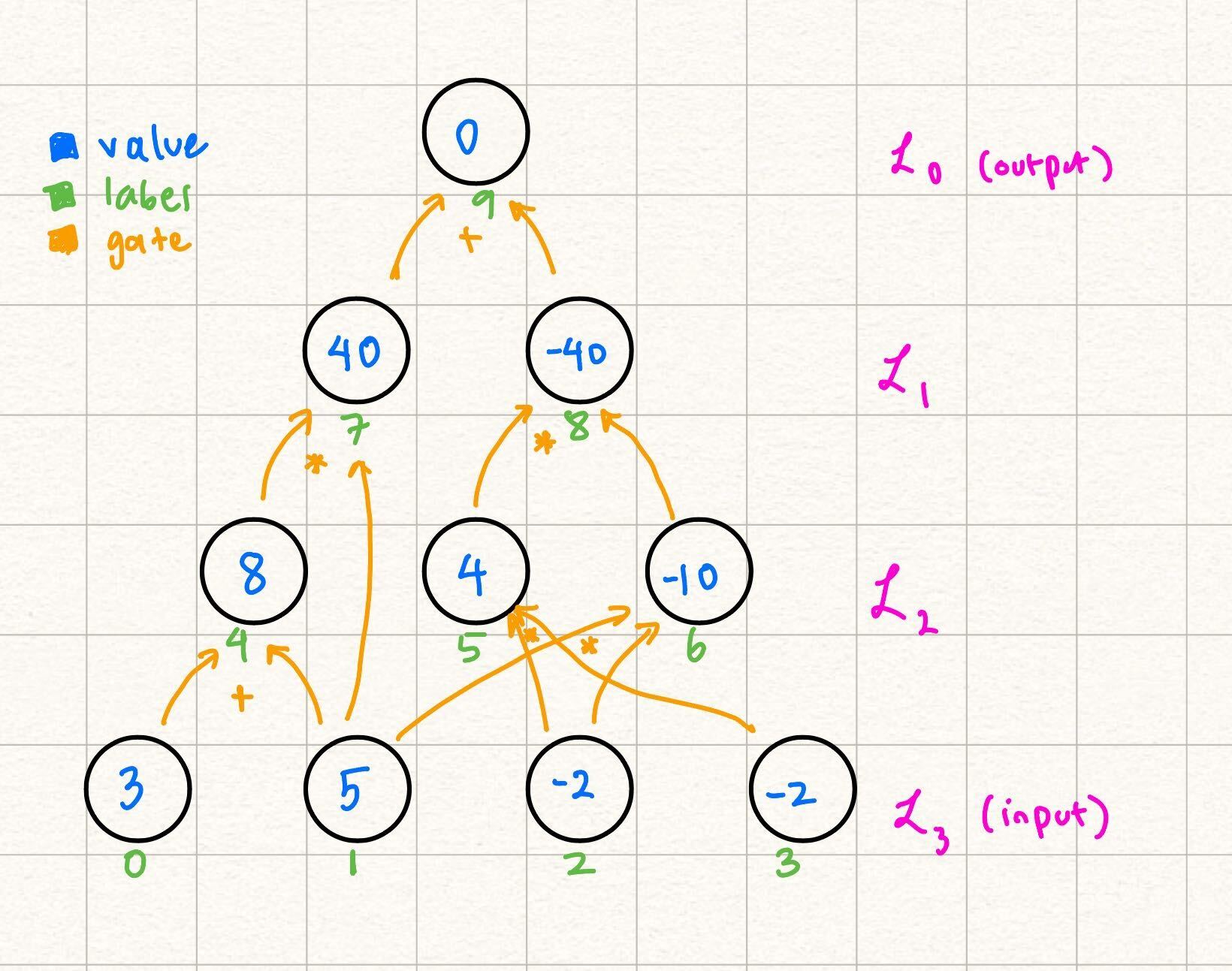

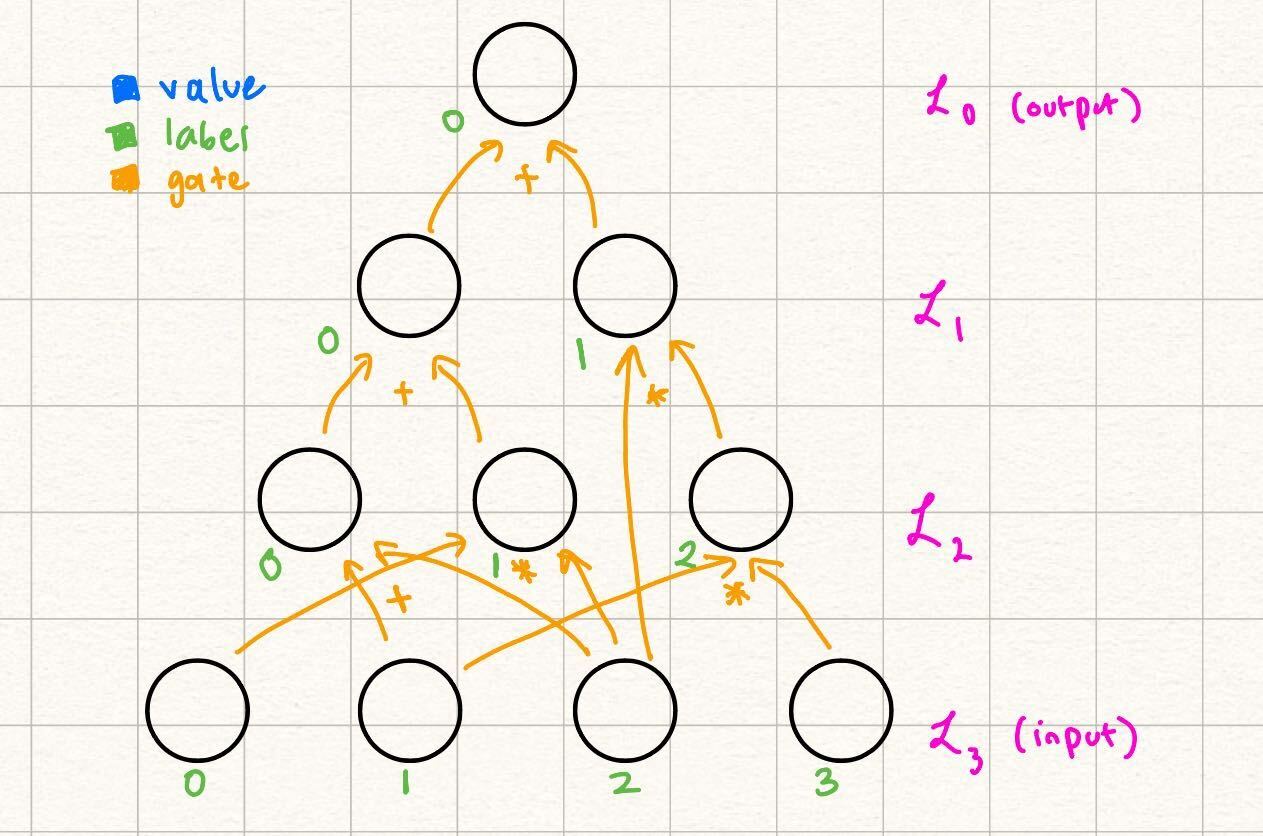

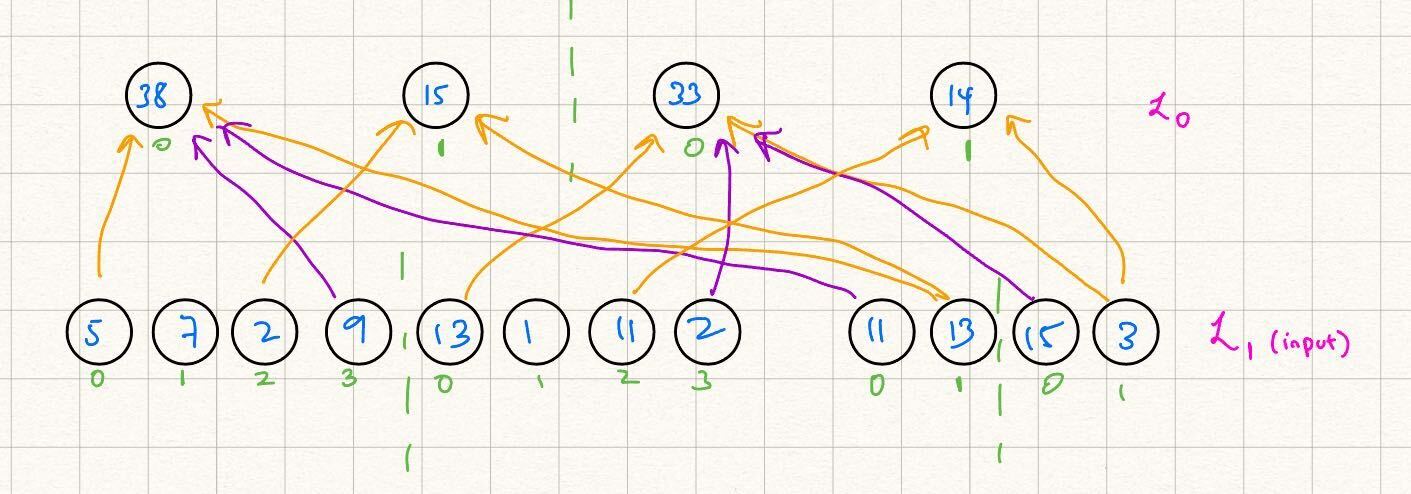

Let's look at the following layered arithmetic circuit with depth = 3:

In this case, and , but . Notice how the circuit naturally falls in "layers" based on the dependencies of values.

Multilinear Extensions (MLEs)

Let be a function . Its multilinear extension is defined such that is linear in each , and where .

Equality MLE

In order to explicitly formulate in terms of , let us define the following indicator function:

Fortunately, has an explicit formula which is linear in each of , or the bits of . Intuitively, if , then each of its bits must be equal. In boolean logic, this is the same thing as saying OR for all of the bits (which is an AND over all of the bits ).

When our inputs this statement can be expressed as the following product: Taking the multilinear extension of simply means allowing for non-binary inputs , because the polynomial is already linear in each variable. Since for all binary we have that , the above definition of is an actual multilinear extension of .

Construction from

We now have a polynomial extension of which happens to be (by construction) linear in the variables (again, denote this function ). We can now define the multilinear extension of any function, as hoped for above:

where are the bits of .

Why is the above a valid multilinear extension of ? The idea here is that when evaluating on any , we have for all (since both and are binary, behaves exactly like the boolean equality function), and thus all the terms in the above summation over are zero except for the term where , where we have , and the value of that term is exactly .

Another nice property of multilinear extensions which can be proven is that they are uniquely defined. I.e., is the only multilinear function in variables which extends .

Example

Let Let us first build a table of evaluations of for

We also build a table for for in terms of :

Then, using the formula for , we get the explicit formula:

.

From here you can verify that when , and that is linear in each of the variables.

Sumcheck

(Most of the content of this section is from Section 4.1 in Proofs, Args, and ZK by Justin Thaler, which has more detailed explanations of the below.)

This section will first cover the background behind the sumcheck protocol, and then provide an introduction as to why this may be useful in verifying the computation of layerwise arithmetic circuits.

The sumcheck protocol is an interactive protocol which verifies claims of the form: In this statement, is not necessarily multilinear, and .

In other words, the prover, , claims that the sum of the evaluations of a function over the boolean hypercube of dimension is Naively, the verifier can verify this statement by evaluating this sum themselves in time assuming oracle access to (being able to query evaluations of in time), with perfect completeness (true claims are always identified by the verifier) and perfect soundness (false claims are always identified by the verifier).

Sumcheck relaxes the perfect soundness to provide a probabilistic protocol which verifies the claim in time with a soundness error of where is the maximum degree of any variable .

The Interactive Protocol

We start with a straw-man interactive protocol which still achieves perfect completeness and soundness in verifier time and prover time Then, we build on this version of the protocol and introduce randomness to achieve verifier time, with a soundness error of

A non-probabilistic protocol

Note that the sum we are trying to verify can be rewritten as such: Let's say sends the following univariate: One way for to communicate to the univariate is to send evaluations of . While can alternatively send coefficients, we focus on this method of defining a univariate and assume sends the evaluations to .

can verify whether is correct in relation to by checking whether In other words, we have reduced the validity of claim that is the sum of the evaluations of over the -dimensional boolean hypercube to the claim that is the univariate polynomial over a smaller sum.

Now the verifier has evaluations to verify. We can similarly reduce this to claims over even smaller summations. Namely, now the prover sends over the following univariates:

and keep engaging in such reductions until is left to verify evaluations of : this is exactly the evaluations of over the boolean hypercube, assuming that has oracle access to (it can query evaluations of in time).

We have transformed the naive solution, where just evaluates the summation on their own, into an interactive protocol. In the next section we will go over how to slightly modify this by adding randomness to significantly reduce the costs incurred by and .

Schwartz-Zippel Lemma

As a brief interlude, let us go over the Schwartz-Zippel Lemma, which we can use to modify the straw-man protocol. It states that if is a nonzero polynomial with degree , then the probability that for some random value sampled from a set is upper-bounded by .

This is can be seen because by the Fundamental Theorem of Alegbra, has at most roots. We take the probability that we randomly sampled one of those roots out of a set of size .

In the case of sumcheck, we consider the polynomial to be over a field , and our randomly sampled element to be uniformly sampled from .

Introducing randomness

Our main blow-up with the straw-man interactive protocol came from the exponentially growing number of claims had to verify, ending up with evaluations of at the end. Instead, if we found a way for the reduction from to claims on (or the reduction from the claim of to claims on ) to be a one-to-one reduction in terms of number of claims, rather than one claim reduced to two claims, would only have to verify claims, and would only have to send over univariate polynomials.

Let us keep the first step the same, where first sends the following univariate polynomial:

Now, checks whether Instead of sending both and , uniformly samples a random challenge from and sends this to sends a single univariate: checks whether This process is repeated iteratively, until finally in the last round, where sends the following:

Assuming the verifier has oracle access to , the verifier can check whether . The difference between this protocol and the naive protocol above is that at each step, instead of individually verifying and , sends a "challenge" in which responds to by sending over the appropriate univariate polynomial. Therefore we have achieved a one-to-one claim reduction, and the verifier having to only verify one equation per round.

Soundness Intuition

We provide brief intuition for the soundness bound from the above protocol. At any step , the prover can cheat by sending a different univariate polynomial instead of the expected such that , but . This allows them to, ultimately, prove a different original statement: that the sum . Because sends to , we can be confident that does not adversarially choose to be one of the roots of . Then, by the Schwartz-Zippel lemma, the probability that happened to be one of the "zeros" of where is the degree of

Example

We do a short example of the sumcheck protocol in the integers. Let rightfully claims that In order to verify this claim, and engage in a sumcheck protocol.

sends the univariate: verifies that Then, samples the challenge and now computes:

checks that Next, samples another challenge and sends it to who then computes and sends Finally, samples another random challenge and checks whether Indeed,

Why Sumcheck?

In the previous section, we introduced the notion of a multilinear extension of a polynomial , which is defined as Notice that naturally, a multilinear extension is defined by taking the sum over a boolean hypercube, which is what sumcheck proves claims over.

In the next section, we will go over how we can encode layers of circuits as multilinear extensions, and prove statements about the output of these layers using sumcheck.

Encoding Layers in GKR

At this point, we have all the puzzle pieces needed to describe the GKR protocol -- layered arithmetic circuits, multilinear extensions, and sumcheck. This section talks about how we can tie all of these concepts together to verify claims on the output of an arithmetic circuit.

Grounding Example

We start with an example layered arithmetic circuit. Throughout this tutorial, we will provide this concrete example while simultaneously providing the generic steps of GKR.

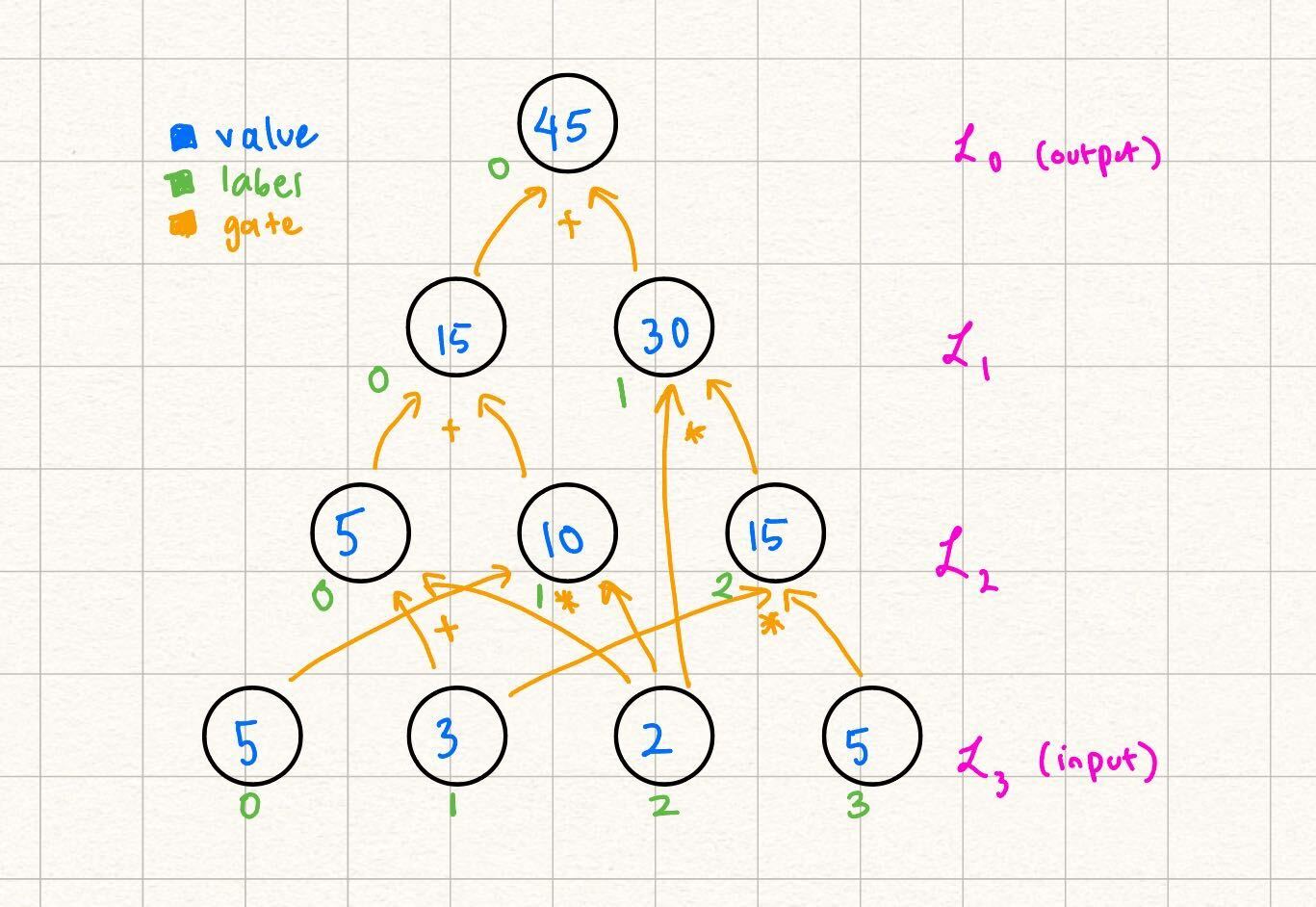

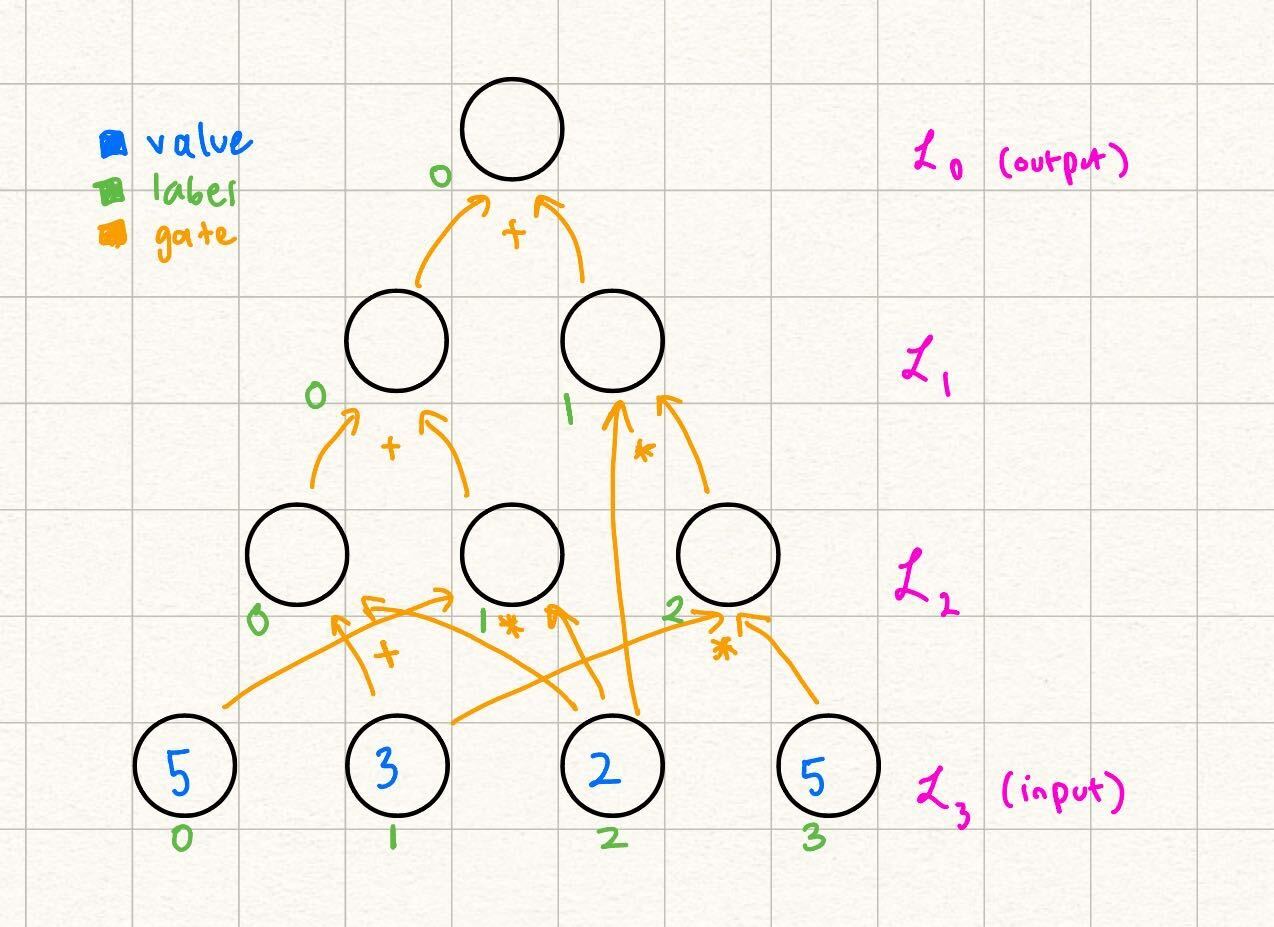

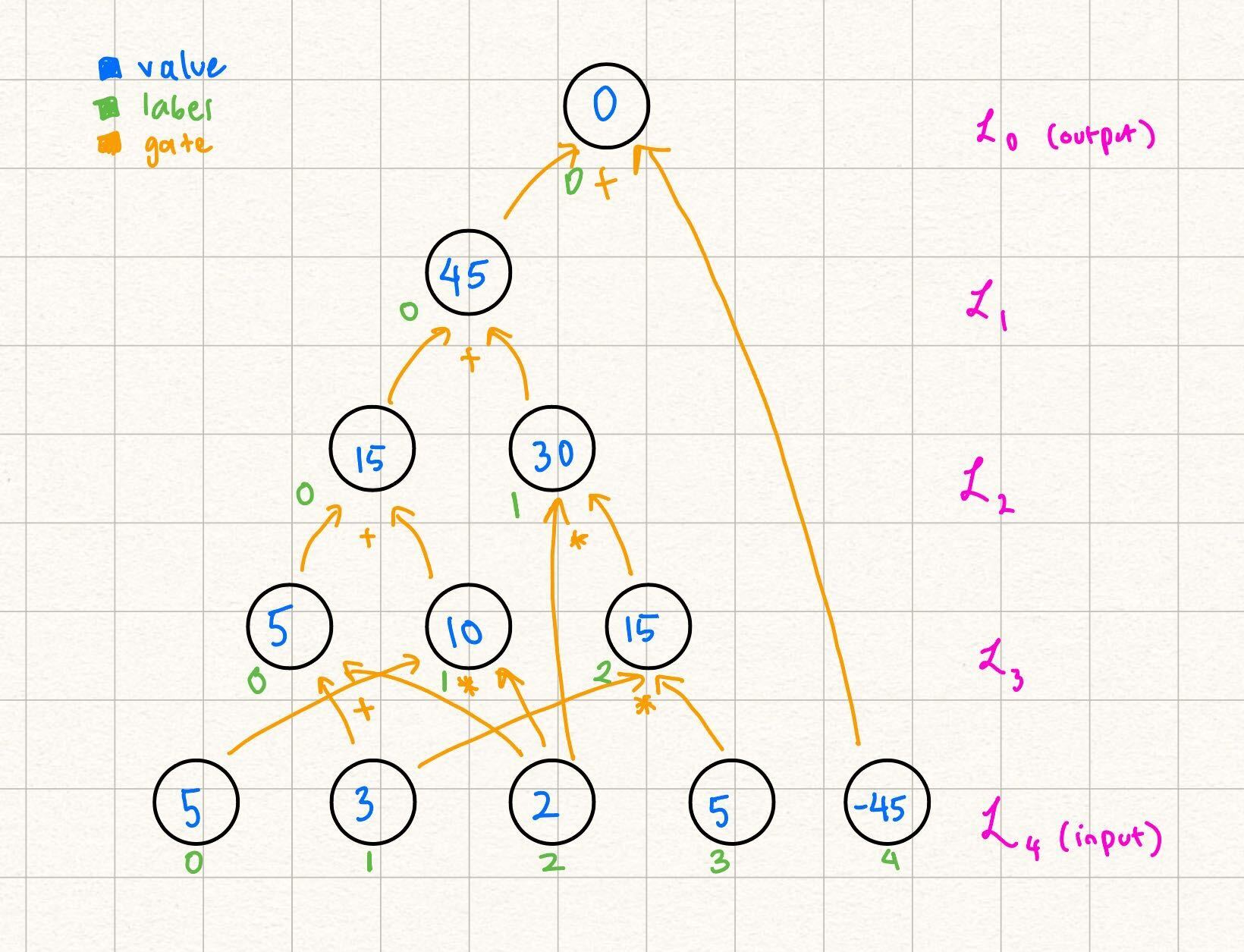

Note some differences from the way this circuit is labeled as opposed to the example in the statement encoding section. Over here, we let the output be a nonzero value for the sake of the example (we explain how to transform any circuit with nonzero output to a circuit with zero output in a future section). Additionally, note that the gate labels start from in each layer, as opposed to the labels being unique throughout the entire circuit in the previous example. Because our gates and are unique per triplet of layers , we can start from in labeling the gates at the start of each layer.

In this example, claims that the output of the following circuit is Note that beyond the values in the input, and the actual structure of the circuit (what we refer to as the circuit description), does not need any more information to verify the output of the circuit by computation:

This is because every node in every layer with can be computed as the result of gates applied to nodes in previous layers.

At a high level, for the rest of this section we focus on encoding layers in two ways: as an MLE of its own, and using its relationship to other layers (via gates). We can equate these two encodings because they are of the same thing (the values in a single layer). With that, we have an equation we can perform a sumcheck over.

Encoding Layer Nodes as an MLE

We start by encoding the input layer in our example, and then show how this extends to the general case. More concretely, we want an MLE such that Although it might not be immediately evident, because we eventually want to invoke the sumcheck protocol, it is useful to consider the inputs as bit-strings rather than integral values.

Example

Therefore, for example, we want because and the bit-string represents . Another way of restating our problem statement of encoding the input layer as some MLE is to say "when , output

Here we can leverage the power of the MLE: or in other words: You can independently verify that at each of the node input label values, outputs the correct value.

General

Note that we conveniently defined the node labels to start from and naturally enumerate the nodes in each layer in our definition of above. This allows us to generally extend the function which represents the nodes of layer into the following MLE: where is the number of nodes in layer .

Encoding Layers using their Relationship to other Layers

Another note we made when presenting the above diagram was that the only information that needs to know immediately is the values of the input itself and the structure of the circuit. This is because the values of the future layers are determined by nodes in previous layers and the gates that connect them. Let's formalize this statement below.

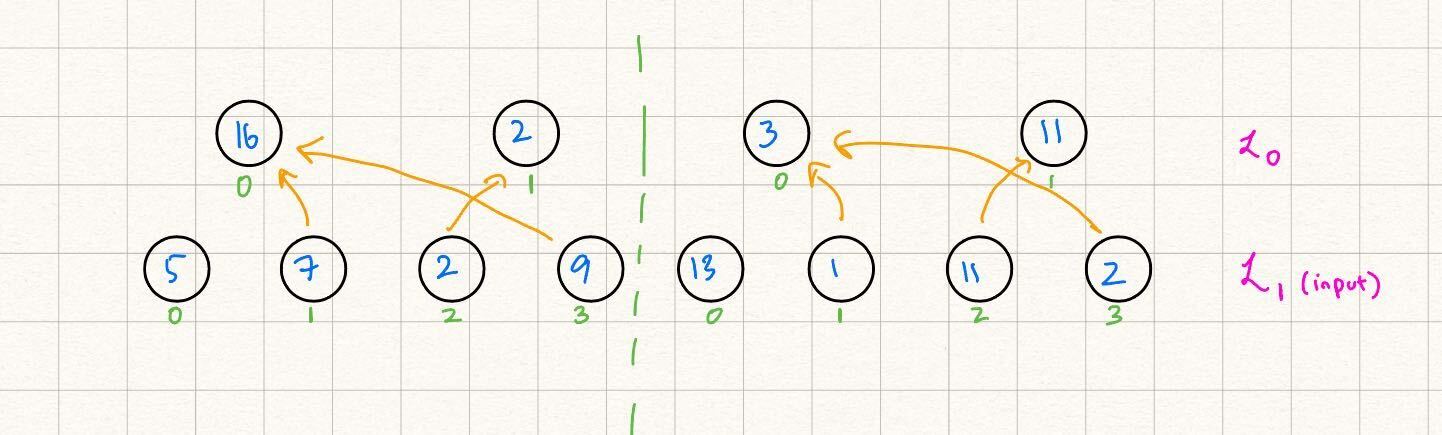

Example

In the running example, let's fill in the layer

We were able to fill this in because:

So, while one way to write the MLE representing , as explained in the previous section, is we can also represent it by its relationship to the nodes in Note that in this definition, we still are linear in the variables

General

Now we go over how to write in terms of for Recall the definition of and . For example, in the case of :

If we use the indicator functions and to translate the example above: where are the number of bits needed to represent the node labels of that respective layer. We know that and can be computed using MLEs for and , so we can rewrite the above as: More detail and examples on transforming these indicator gate functions into MLEs are described in the section on canonic GKR.

Using the Equivalence between Layer Encodings

Now we have enough information to show how we can reduce claims on one layer to claims on the output of an MLE encoding a source layer (closer to the circuit input layer) for that layer.

Example

We start with the MLE encoding the output. claims that the output of the circuit is , i.e., . Then, at any random point challenges with, say , because is a constant function, an honest claims that .

Another way, as expressed above to write is as:

Note that while we expicitly write to maintain consistency between earlier examples, in this case, because there is only one output, there are no variables. Therefore, and are constant functions, and their extensions are equal to their value in their first position: and .

and engage in a sumcheck protocol to verify this claim of the sum of a polynomial over the boolean hypercube. Recall that sumcheck requires binding the variables that the sum is over (in this case, ), one by one, with random challenges.

If we follow the sumcheck protocol as is, at the end, is bound to and is bound to . Let's say the prover's final univariate is and the verifier's final challenge is Then, we end with the final claim:

knows the structure of the circuit, so they can compute on their own. Additionally, is publically computable, so computes that on their own as well. Normally, sumcheck would require make a query to an "oracle" to verify the claimed values and .

However, instead we say that "reduces" the claim that to two claims on

Similarly, has a relationship to MLEs in later layers, so the sumcheck on will reduce to claims on these MLEs, eventually propagating to claims on the input layer.

For another example of claim reduction for structured GKR, see this section.

General

In general, GKR works very similarly to the example above. We cover the case where expects the output of the circuit to be . receives a challenge from and claims that the MLE representing still evaluates to over that random point. I.e., claims that Using the encoding of using later layers, reduces its claim on the output of the circuit to evaluations of MLEs representing future layers.

Note that there is an exponential blow-up of claims when reducing claims on one layer to the next. We describe a protocol to aggregate claims (and therefore achieve a one-to-one reduction) in the claims section.

Circuit Description

Throughout this section, we refer to using the description of the circuit in order to evaluate the gates or to understand the layerwise relationships on their own. The circuit description is something agreed upon beforehand with and and visible to both parties -- it is the "shape" of the circuit, which includes how many nodes each layer contains, the number of layers, and which gates connect nodes from layer to layer.

Therefore, the circuit description of our example circuit is this:

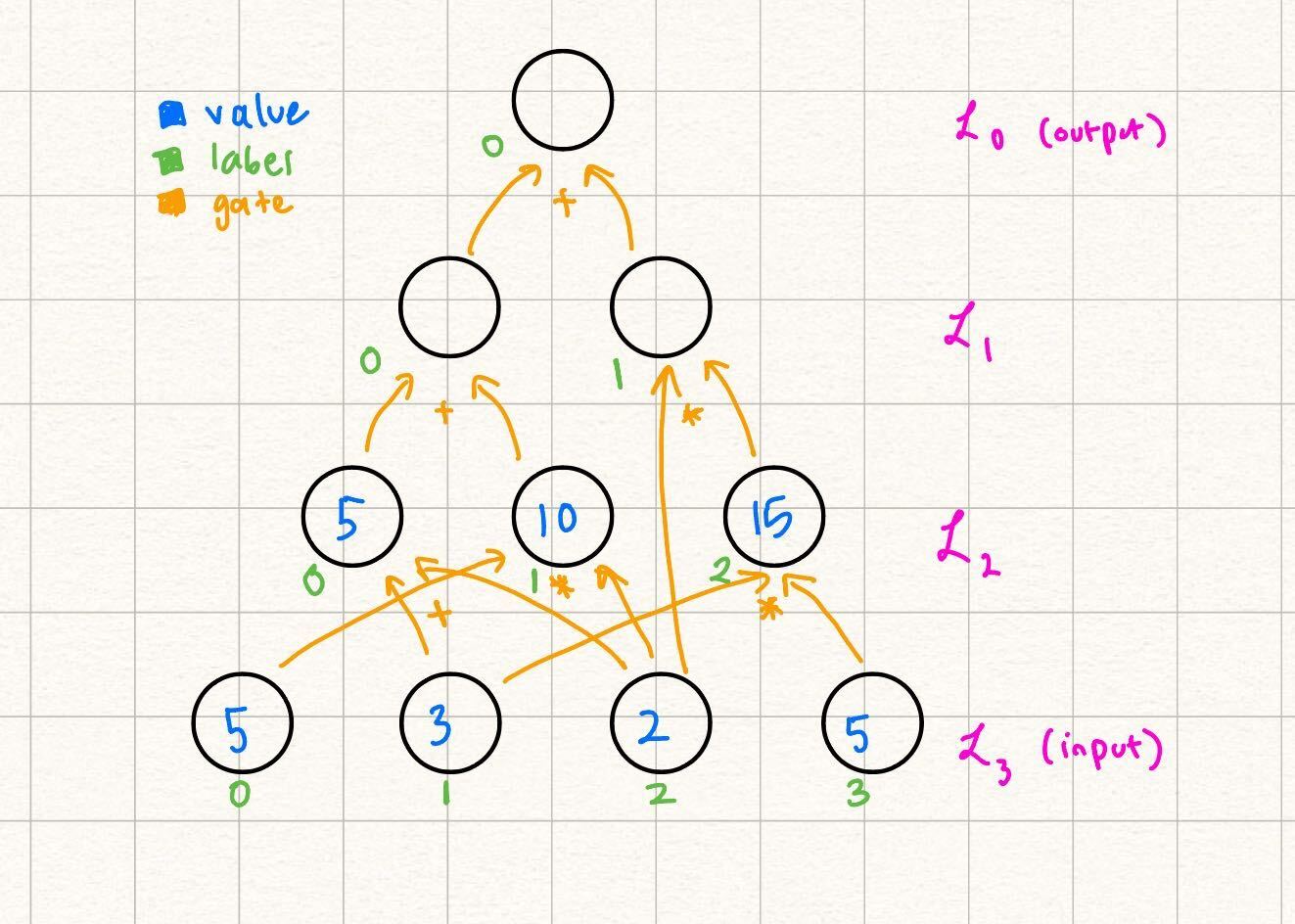

Note: Transforming a Circuit to have Zero Output

In Remainder, expects circuits to have output . This is because certain types of circuits (such as those resulting from LogUp) require the output to specifically be , and needs to specifically verify this fact.

If a circuit does not have output , one way to transform this is to add the negative of the expected output to the input. The last layer of the circuit can be the sum of this expected output, and the actual output of the circuit. This results in a circuit with the output layer evaluating to . We show this transformation applied to our example above:

GKR Theory Overview

Read the introduction and ready to dive into some deeper GKR theory concepts? Let's go!

Structured ("Sector") GKR

Source: Tha13, section 5 ("Time-Optimal Protocols for Circuit Evaluation").

Review: Equality MLE

We begin by briefly recalling the MLE (see this section for more details). We first consider the binary string equality function , where

This function is if and only if and are equal as binary strings, and otherwise. We can extend this to a multilinear extension via the following -- consider , where

Structured Layerwise Relationship

See Tha13, page 25 ("Theorem 1") for a more rigorous treatment. Note that Remainder does not implement Theorem 1 in its entirety, and that many circuits which do fulfill the criteria of Theorem 1 are currently not expressible within Remainder's circuit frontend.

Structured layerwise relationships can loosely be thought of as data relationships where the bits of the index of the "destination" value in the 'th layer are a (optionally subset) permutation of the bits of the index of the "source" value in the 'th layer for . As a concrete example, we consider a layerwise relationship where the destination layer is half the size, and its values are the element-wise products of the two halves of the source layer's values: Let represent the MLE of the destination layer, and let represent the MLE of the source layer.

Let the evaluations of over the hypercube be . Then we wish to create a layerwise relationship such that the evaluations of over the hypercube are . We can actually write this as a simple rule in terms of the (integer) indices of as follows:

If we allow for our arguments to be the binary decomposition of rather than itself, we might have the following relationship:

where is the binary representation of and is the binary representation of . This is in fact very close to the exact form-factor of the polynomial layerwise relationship which we should create between the layers -- we now consider the somewhat un-intuitive relationship

One way to read the above relationship is the following: for any (binary decomposition) , the value of the 'th layer at the index represented by should be . We are summing over all possible values of the hypercube above, , and for each value we check whether the current iterated hypercube value "equals" the argument value. If so, we contribute to the sum and if not, we contribute zero to the sum.

In this way we see for that all of the summed values will be zero except for when are exactly identical to , and thus only the correct value will contribute to the sum (and thus the value of ).

As described, the above relationship looks extremely inefficient in some sense -- why bother summing over all the hypercube values when we already know that all of them will be zero because will evaluate to zero at all values except one?

The answer is that it's not enough to only consider for binary , as our claims will be of the form , where , and is the multilinear extension of (see claims section for more information on prover claims). Another way to see this is that the above relationship is able to be shown for each , but we want to make sure that the relationship holds for all . Rather than checking each index individually, it's much more efficient to check a "random combination" of all values simultaneously by evaluating at a random point . We thus have, instead, that

Since is identical to (and similarly for and ) everywhere on the hypercube, the above relationship should still hold for all binary . Moreover, the above relationship is now one which we can directly apply sumcheck to, since we have a summation over the hypercube!

But wait, you might say. This still seems wasteful -- why are we bothering with this summation and polynomial? Why can't we just have something like

Unfortunately the above relationship cannot work, as are linear on the LHS and quadratic on the RHS. The purpose of the summation and polynomial is to "linearize" the RHS and quite literally turn any high degree polynomial (such as ) into its unique multilinear extension (recall the definition of multilinear extension).

We see that the general pattern of creating a "structured" layerwise relationship is as follows:

- First, write the relationship in terms of the binary indices of values between each layer. In our case, .

- Next, replace on the LHS of the equation with formal variable , and allow the LHS to be a multilinear extension. We now have on the LHS.

- Next, replace on the RHS of the equation with boolean values and add an predicate between , and add a summation over all values. Additionally, extend all to their multilinear extensions (this is importantly only for sumcheck):

Structured "Selector" Variables

Some relationships between layers are best expressed piece-wise. For example, let's say that we have a destination layer, , and a source layer of the same size, , where we'd like to square the first two evaluations but double the last two.

In other words, if has evaluations over the boolean hypercube, then should have evaluations . If we follow our usual protocol for writing the layerwise relationship here, we would have something like the following for the "integer index" version of the relationship:

We notice that in binary form, whenever (and when ). We can thus re-write the above as

In other words, when the second summand on the RHS is zero, and the first summand is just since we already know that , and vice versa for when . At a first glance, this may look similar to the earlier example in which we took the products of adjacent pairs of layer values, but the two are not the same --

- First, the current setup is semantically quite different; in the previous example we applied a binary "shrinking" transformation between the source and destination layers by multiplying pairs of values, while in the current example we are "splitting" the circuit into two semantic halves and applying a different unary operation element-wise to each half.

- Second, the current setup actually has its variable outside of the argument to an MLE representing data in a previous layer. This is precisely what allows us to "select" between the two semantic halves of the circuit and compute an element-wise squaring in the first and a doubling in the second.

Applying the third transformation rule from above and extending everything into its multilinear form, we get

However, now the observation that should only apply to variables which are nonlinear on the RHS is helpful here -- notice that although as a variable would be quadratic on the RHS, is linear and can thus be removed from the summation altogether and replaced directly with :

This layerwise relationship form-factor is called a "selector" in Remainder terminology and in general refers to an in-circuit version of an "if/else" statement where MLEs representing the values of layers can be broken into power-of-two-sized pieces.

Why Structured Circuits?

Compared to canonic GKR, structured circuits are good for two reasons -- verifier runtime and circuit description size. Note that every layerwise relationship which can be expressed as a structured layer (using ) can be written as an equivalent series of and gate layers.

To see why structured layers are good for circuit description size, we compare the following layer-wise relationships which describe the same circuit wiring pattern, but with different verifier cost and circuit description complexities (let and for shorthand). Firstly, the structured version, which computes an element-wise product between each pair of evaluations:

And secondly, the multiplication gate version:

We first consider the verifier runtime for both. Note that the sumcheck verifier performs operations per round of sumcheck, plus the work necessary for the oracle query. In the structured relationship's case, there are rounds of sumcheck, and assuming that get bound to , the oracle query which the verifier must evaluate is of the form

where is the 'th univariate polynomial which the prover sends during sumcheck. The prover sends the claimed values for both and , and so the verifier doesn't do any work there. The verifier additionally evaluates on its own, which it can do in time.

Next, we consider the verifier runtime for the multiplication gate case: let be bound to and let be bound to during sumcheck. The oracle query is then

Similarly to the structured case, the prover sends claimed values for and , and so the verifier doesn't have to do any work here. However, the verifier must also evaluate on its own. This requires time linear to the sparsity of the polynomial, i.e. in this example, since there are nonzero multiplication gates (one for each pair of values in layer ).

A circuit description size comparison between the two can be seen in a very similar light. In particular, the representation of requires just words to store (assuming each word can hold an -bit value), as we simply enumerate the indices between the 's and the 's. On the other hand, storing the sparse representation of required for linear-time proving requires storing all nonzero evaluations, i.e. such indices in the above example (although one might argue that the representation is quite structured and can therefore be further compressed).

A note on claims

The above example (and other similar layerwise relationships) give us a further prover speedup through the structure of the claims which arise from the oracle query during sumcheck. In particular, the claims which the prover makes to the verifier in the structured case are as follows:

These claims can be aggregated with almost no additional cost to the prover and verifier, as the first challenges are identical between the two and the last challenges are precisely a and a . In particular, the verifier can simply sample and have the prover instead show that

On the other hand, the claims generated by the multiplication gate version of the layer above are in the form

These claims have no challenges in common, and can only be aggregated through interpolative or RLC claim aggregation, both of which are significantly more expensive than the above method.

Costs

In general (note that this does not capture all possible structured layer cases, but should be enough to give some intuition on the prover/verifier/proof size costs for most structured layers), let us assume that our layerwise relationship can be expressed in the following manner -- In other words, we have a layerwise relationship over variables, where the values in are a function of those in layers , where , such that we have total summand "groups" of MLEs over variables of size up to , i.e. the total polynomial degree in each of the is .

The prover costs are as follows:

-

For simplicity here, we assume that the prover has access to any value in (note that these evaluations must be either precomputed in linear time, e.g. Tha13, or can be streamed in linear time in a clever way, e.g. Rot24).

-

Additionally, we assume that the prover has access to any value in any , since the prover presumably knows all of the circuit values ahead of time.

-

Finally, we assume that the prover can use the "bookkeeping table folding" trick from Tha13 to compute both from and from in field operations.

-

We thus see that in the first round of sumcheck, the prover must do the following:

- Evaluate each of the terms in the summation for every and sum them together. Each evaluation takes field operations, as there are summands and each requires multiplications.

- Since there are values of , the above costs field operations. This is the total cost for the prover to compute the claimed sum for the first round.

- Next, the prover must evaluate the RHS of the sumchecked equation at in the place of to compute the univariate sumcheck message. Each evaluation of , similarly to the above, costs field operations.

- The total cost for the prover to compute the claimed sum + univariate message in the first round is thus field operations.

-

We can generalize the above to the 'th round of sumcheck (let for the first round) by noting that rather than variables, there are variables which are being summed over in the outer sum. Since the other values remain constant, the prover's total cost is simply .

-

Finally, as mentioned earlier, the prover can generate the necessary precomputed values from the 'th round from those of the 'th round in , as there are MLEs (including the polynomial) which need their bookkeeping tables to be "folded" in .

-

Putting it altogether, the prover's total cost across all sumcheck rounds is thus

-

Since the above is a geometric series in , we have that the prover's total cost across all rounds is simply

The proof size is as follows:

- For each of the rounds of sumcheck, the prover must send over a degree univariate polynomial to the verifier. Additionally, the prover must send the original sum (although this is actually free in GKR since the verifier already has the prover-claimed sum implicitly through the prover's claim from a previous sumcheck's oracle query).

- Finally, the prover must send over each of its claimed values for the at the end of sumcheck. There are at most claims.

- The proof size is thus simply field elements.

The verifier runtime is as follows:

- For each round of sumcheck, let the prover's univariate polynomial message be . The verifier samples a random challenge and checks whether

- Since the verifier can evaluate and in and performs this check for each of the rounds of sumcheck, they can compute all the intermediate checks in .

- During the final oracle query, the verifier must check whether

- The verifier can compute on its own in , and has access to each of the prover-claimed values for . It can thus compute the RHS of the above in .

- The verifier's total runtime is thus

c# Canonic GKR See XZZ+19, ZLW+20 for more details.

"Gate"-style layerwise relationship

Unlike the structured wiring pattern described in the previous section, "gate"-style layerwise relationships allow for an arbitrary wiring pattern between a destination layer and its source layer(s). In general, these layerwise relationships are defined via indicator functions (these function like the function in structured layerwise relationships, but allow for input wires whose indices have no relationship to those of the output wire). Consider, for example, the canonic layerwise GKR equation, which defines the relationship between a previous layer's MLE ( below) and the current layer's MLE ( below): We define three types of gate layers within Remainder, although they are all quite similar in spirit.

Notation

- Let denote the number of variables the MLE representing layer has (in other words, layer of the circuit has values).

- Let be the MLE corresponding to values in the layer of the circuit which is the "destination" of the gate polynomial relationship.

- Let be the MLE corresponding to values in (one) layer of the circuit which is the "source" of the gate polynomial relationship. Note that always.

- Similarly, let be the MLE corresponding to values in (another) layer of the circuit which is a second "source" of the gate polynomial relationship. Note that always.

Identity Gate

Identity gates are defined in the following way: In other words, is if and only if there is a gate from the 'th value in the 'th layer to the 'th value in the 'th layer. These can be thought of as "routing" gates or "copy constraints", as they directly pass a value from one layer to another. The MLE of the identity function above is defined as follows: The polynomial relationship between the "destination" layer 's MLE and the "source" layer 's MLE is as follows: Assuming that gets bound to during sumcheck, this layer produces two claims -- one on and one on . The former can be checked by the verifier directly (since it knows the circuit wiring and uses the definition of above), and the latter is proven by sumcheck over layer .

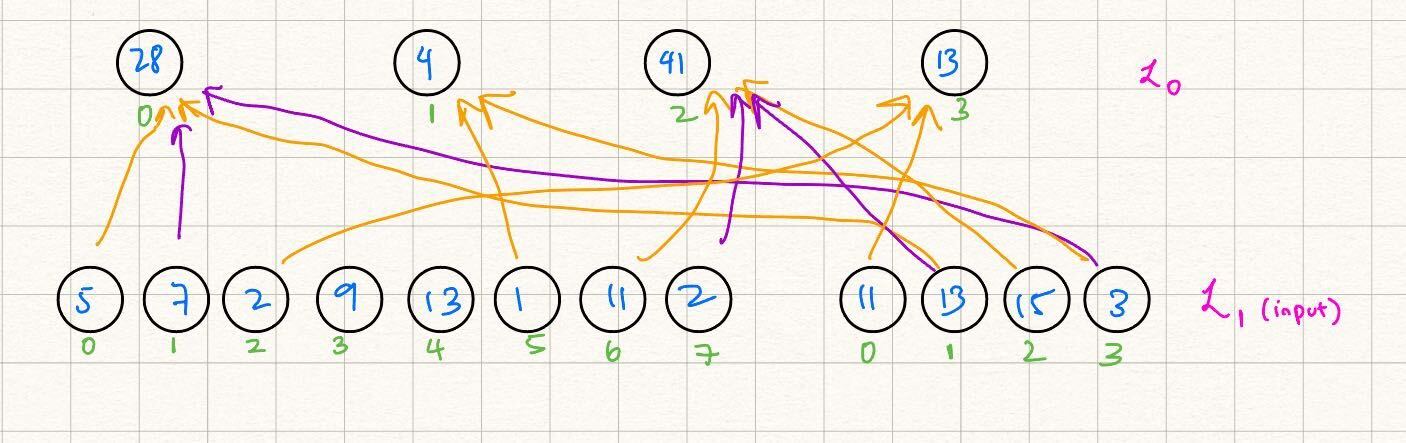

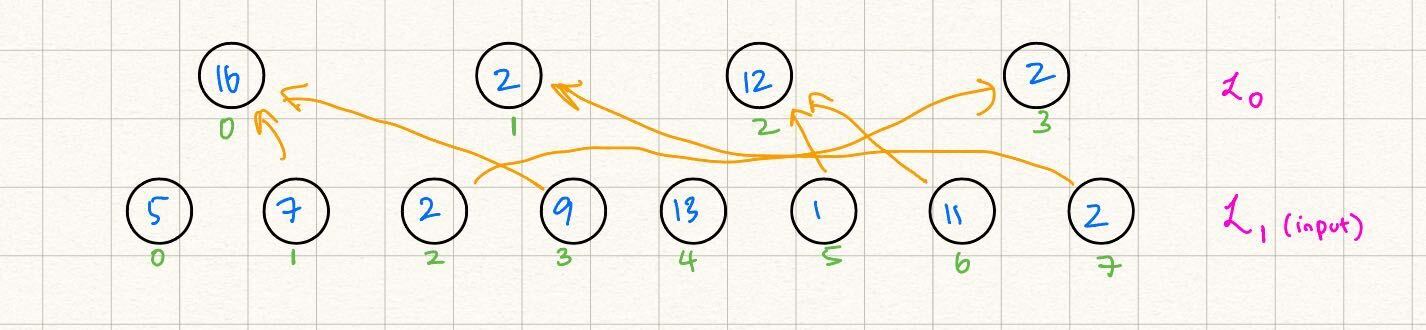

Example

We start with a "source" MLE over two variables with four evaluations, and wish to obtain a circular-shifted version of the evaluations of this MLE in layer , i.e. .

For example, let's say that the evaluations of are . We wish for those of to be e.g. . To do this, we can list the "nonzero" identity gate indices, i.e. , such that :

- : the zeroth evaluation of layer is equivalent to the first evaluation of layer .

- : the first evaluation of layer is equivalent to the second evaluation of layer .

- : similar reasoning as above.

- : similar reasoning as above.

For all other tuples over binary values we have that .

Costs

Over here, we go through some of the costs for the prover runtime, proof size, and verifier runtime when performing sumcheck over an identity gate layer. In order to provide some intuition, we analyze the costs of a particular example, which may not encapsulate the general example for identity gate layers.

Let us recall the identity gate sumcheck equation: We can rewrite this as: As observed in XZZ+19, we only need to sum over the wirings which are non-zero (i.e., there exists a re-routing from label in layer to label in layer ). Call the set of non-zero wirings as (here, we say that , i.e. a constant number of wires for each input layer and output layer value). We can rewrite the summation as:

The prover cost for sumcheck over an identity gate layer is as follows:

- The prover must first compute the evaluations of . By summing over the non-zero wirings in , XZZ+19 shows us how to compute an MLE with evaluations of this product in time This involves first pre-computing the table of evaluations of using the dynamic-programming algorithm in Tha13, and then appropriately summing over to fold in the evaluations of

- Next, the prover must compute sumcheck messages for the above relationship. The degree of each sumcheck message is , and thus the prover sends evaluations per round of sumcheck. Since we are sumchecking over , there are rounds of sumcheck and thus the prover cost is for the 'th round of sumcheck. The total prover sumcheck cost is thus

- Letting be a constant, the total prover runtime (pre-processing + sumcheck) is

The proof size for sumcheck over identity gate is as follows:

- There are total sumcheck rounds, each with the prover sending over evaluations for a quadratic polynomial. The proof size is thus field elements, plus extra for the final claim on .

The verifier cost for sumcheck over identity gate is as follows:

- The verifier receives sumcheck messages with evaluations each, and each round it must evaluate those quadratic polynomials at a random point. Its runtime is thus with very small constants.

Add Gate

The concepts for addition and multiplication gates are very similar to that of identity gate above. For add gate, we have the binary wiring indicator predicate: Here, we have that if and only if the 'th value in the 'th layer and the 'th value in the 'th layer sum to the 'th value in the 'th layer. The MLE of is similar to that of : and the polynomial relationship is defined very similarly to that of identity gate: Assuming that gets bound to and gets bound to during sumcheck, a claim on this layer results in three total claims: one on (which the verifier can compute from the circuit description and therefore check on its own), one on , and one on .

Example

We start with two "source" MLEs, over two variables with four evaluations each, and wish to add each value in the first with its "complementary value" in the second. The result should be the MLE representing layer , i.e. .

For example, let's say that the evaluations of are and those of are . We wish to add to , to , and so on. Then our "nonzero gate tuples" are as follows:

- : the zeroth value in the 'th layer is equivalent to the sum of the zeroth value in the 'th layer and the third value in the 'th layer.

- : the first value in the 'th layer is equivalent to the sum of the first value in the 'th layer and the second value in the 'th layer.

- : similar reasoning to the above.

- : similar reasoning to the above.

For all other binary tuples we have that , and our resulting MLE's evaluations should be as follows: .

Costs

Over here, we go through some of the costs for the prover runtime, proof size, and verifier runtime when performing sumcheck over an add gate layer. In order to provide some intuition, we analyze the costs of a particular example, which may not encapsulate the general example for add gate layers.

Let us recall the add gate sumcheck equation: We can rewrite this as: As observed in XZZ+19, we only need to sum over the wirings which are non-zero (i.e., there exists a an addition from label in layer and label in layer to label in layer ). Call the set of non-zero wirings as . We can rewrite the summation as:

Mul Gate

Multiplication gate is nearly identical to addition gate. For mul gate, we have the binary wiring indicator predicate: Here, we have that if and only if the the 'th value in the 'th layer equals the product of the 'th value in the 'th layer with the 'th value in the 'th layer. The MLE of is identical to that of : and the polynomial relationship is defined nearly identically to that of gate: Assuming that gets bound to and gets bound to during sumcheck, a claim on this layer results in three total claims: one on (which the verifier can check on its own), one on , and one on .

Example

We start with two "source" MLEs, over two variables with four evaluations each, and wish to accumulate (add up) the product of the 0th and 2nd evaluations with that of the 1st and 3rd evaluations, and place this into the 0th evaluation in the resulting MLE. The result should be the MLE representing layer , i.e. , whose evaluations are all zero except for its 0th evaluation.

For example, let's say that the evaluations of are and those of are . We wish to multiply and , and and and have those be the zeroth evaluation of the resulting MLE, i.e. . We then wish to multiply and , and and and have those be the first evaluation of the resulting MLE, i.e. .

Then our "nonzero gate tuples" are as follows:

- : The zeroth value in the 'th layer multiplied by the first value in the 'th layer contributes to the zeroth value in the 'th layer.

- : The first value in the 'th layer multiplied by the zeroth value in the 'th layer contributes to the zeroth value in the 'th layer.

- : similar reasoning to the above.

- : similar reasoning to the above.

For all other binary tuples we have that , and our resulting MLE's evaluations should be as follows: . Note here for that we are able to add multiple products to each output value in the 'th layer, and that the same is true for both and . In other words, we actually have unlimited addition fan-in and degree-2 multiplication fan-in.

Costs

Over here, we go through some of the costs for the prover runtime, proof size, and verifier runtime when performing sumcheck over a mul gate layer (note that costs for add gate are very similar). In order to provide some intuition, we analyze the costs of a particular example, which may not encapsulate the general example for add gate layers.

Let us recall the mul gate sumcheck equation: We can rewrite this as: As observed in XZZ+19, we only need to sum over the wirings which are non-zero (i.e., there exists a an addition from label in layer and label in layer to label in layer ). Call the set of non-zero wirings as (we assume that there are at most nonzero mul gate values). We can rewrite the summation as:

The prover cost for sumcheck over a mul gate layer is as follows:

- The prover must first compute the evaluations of for where . XZZ+19 splits this pre-processing into two phases (note that proving the gate layer follows the same strategy). First, we precompute (or stream) the values in in .

- Next, we compute the "phase 1" preprocessing, where we sumcheck over the variables. Here, we can directly evaluate while "folding" by summing over the variables. Similarly, in the second phase, when we compute sumcheck messages over and already have evaluations for , we can "fold" by summing over the variables. Both of these preprocessing steps take time.

- After preprocessing, the prover must compute sumcheck messages for the above relationship. Similarly to the preprocessing step above, sumcheck is done in two phases. First, the prover binds the variables, and then it binds the variables. The degree of each sumcheck message is , and thus the prover sends evaluations per round of sumcheck (this is the same for add gate). Since we are sumchecking over and , there are rounds of sumcheck and thus the prover cost is for the 'th round of sumcheck. The total prover sumcheck cost is thus

- Letting be a constant, the total prover runtime (pre-processing + sumcheck) is

The proof size for sumcheck over mul gate layer is as follows:

- There are + total sumcheck rounds, each with the prover sending over evaluations for a quadratic polynomial. The proof size is thus field elements, plus extra for the final claims on and .

The verifier cost for sumcheck over mul gate layer is as follows:

- The verifier receives sumcheck messages with evaluations each, and each round it must evaluate those quadratic polynomials at a random point. Its runtime is thus with very small constants.

GKR Claims

Claim definition

"Claims" in GKR are statements which the prover has yet to show correctness for. As described earlier, the first step in proving the correctness of a GKR circuit (after sending over all circuit inputs, both public and committed) is to take the circuit's (public) output layer and send over all of its evaluations to the verifier.

For example, let's say that we have a circuit whose output layer contains 4 elements, i.e. whose representative MLE can be described by . Additionally, let's say that these evaluations are , such that

These four equalities above are actually the first claims whose validity the prover wishes to demonstrate to the verifier. The verifier doesn't know what the true values of are, of course, but would be able to check each of these relationships with the prover's help via sumcheck. This would be rather expensive, however, as the number of claims is exactly equal to the number of circuit outputs/evaluations within the circuit's output layer. Instead, the verifier can sample some randomness and have the prover prove the following:

Note that the above follows precisely from the definition of a multilinear extension (MLE), and it can indeed be viewed exactly as the evaluation of at the random points . The protocol takes a slight soundness hit here, as a cheating prover might get away with an incorrect circuit output (say, , but ), but the probability of such an occurrence is , as non-identical MLEs only intersect at exactly one point via the Schwartz-Zippel lemma.

In general, claims take the following form:

In other words, the prover wishes to convince the verifier that the evaluation of the MLE representing the 'th layer at the challenge is .

Claim Propagation

For another example of claim propagation/reduction, see this section. Note that the below example uses a structured GKR relationship while the other example uses a canonic GKR relationship.

Recall the general sumcheck relationship for a function ; the prover claims that the following relationship is true for :

Assuming that are bound to during the sumcheck process, the final verifier check within sumcheck is the following, where the RHS must be an "oracle query", i.e. the verifier must know that the evaluation of on is correct:

How does this oracle query actually get evaluated in GKR? The answer is claims and sumcheck over claims for a previous layer. Specifically, let's consider the following relationship (see structured GKR section for more information about the polynomial and this kind of layerwise relationship):

This is the polynomial relationship between layer and layer of a circuit where the 'th layer's values are exactly those of the 'th layer's values squared. For example, if the evaluations of are then we expect the evaluations of to be .

The prover starts with a claim

for , and wishes to prove it to the verifier. It does so by running sumcheck on the RHS of the above equation, i.e.

Let be bound to during the rounds of sumcheck. Additionally, let be the univariate polynomial the prover sends in the 'th round of sumcheck. The oracle query check is then

The verifier is able to compute on its own in time, but unless is an MLE within an input layer of the GKR circuit, they will not be able to determine the value of . Instead, the prover sends over a new claimed value , and the verifier checks that

The only thing left to check is whether . Notice, however, that this now a new claim on an MLE residing in layer , and that we started with a claim on layer . In other words, we've reduced the validity of a claim on layer to that of a claim on layer , which is the core idea behind GKR: start with claims on circuit output layers, and reduce those using sumcheck to claims on earlier layers of the circuit. Eventually all remaining claims will be those on circuit input layers, which can be directly checked via either a direct verifier MLE evaluation for public input layers, or a PCS evaluation proof for committed input layers.

Claim Aggregation

In the above example, we reduced a single claim on layer to claim(s) on MLEs residing in previous layers. What happens when there are multiple claims on the same layer, e.g.

One method would be to simply run sumcheck times, once for each of the above claims, and reduce to separate claims on MLEs residing in previous layers. This strategy, however, leads to an exponential number of claims in the depth of the circuit, which is undesirable.

Instead, Remainder implements two primary modes of claim aggregation, i.e. methods for using a single sumcheck to prove the validity of many claims on the same MLE.

RLC (Random Linear Combination) Claim Aggregation

Additional reading: See XZZ+19, page 10 ("Combining two claims: random linear combination").

The idea behind RLC claim aggregation is precisely what it sounds like: the prover shows that a random linear combination of the claimed values indeed equals the corresponding random linear combination of the summations on the RHS of e.g. the third equation in the above section. The implementation of RLC claim aggregation within Remainder works for structured layers and gate layers, but not for matrix multiplication layers or input layers (as explained below).

We defer to the corresponding pages for more detailed explanations of the layerwise relationships, but review their form factors here and show how RLC claim aggregation can be done for each here.

Structured Layers

We start with structured layers, and use the same example relationship from above:

For simplicity, we aggregate two claims rather than claims, but the methodology generalizes in a straightforward fashion. Our aggregated claim is constructed as follows:

Similarly, we take an RLC of the summations and create a new summation to sumcheck over (we let and for concision):

For structured layers, in other words, the prover and verifier simply take a random linear combination of the claims and perform sumcheck over a polynomial which is identical to the original layerwise relationship polynomial but with the term replaced with an RLC of terms in the same manner as the RLC of the original claims.

Gate Layers

A similar idea applies to gate layers. We use mul gate as the example layerwise relationship here:

Again, we aggregate just two claims for simplicity, although the idea generalizes very naturally to claims:

The polynomial relationship to run sumcheck over is constructed using a similar idea as that of structured layers:

Rather than taking a linear combination of the polynomials, we instead take a linear combination of the polynomials.

Costs

The prover costs for RLC claim aggregation are as follows -- assume that we are working with a structured layer (the analysis is similar for gate layers) and that the degree of every sumcheck variable is (in the above example for a structured layer, ). Additionally, assume that we have claims over a layer with variables.

- As shown above, RLC claim aggregation for structured layers simply involves "factoring out" the term between each of the 's and the 's. Rather than multiplying the structured polynomial relationship by a single , we multiply by an RLC of terms.

- For each additional term, the prover incurs an additional evaluations worth of work (across a single sumcheck round). Evaluating can be done in time by the prover for variables, and thus the total cost (for claims) is

- across all rounds of sumcheck. The total prover runtime is thus .

The proof size is identical to that of the single-claim sumcheck case, since the degree of the sumcheck messages do not change.

Finally, the verifier cost is slightly increased. Specifically, during intermediate rounds of sumcheck the verifier does not do any additional work (compared to the single-claim sumcheck case), but during the oracle query the verifier must evaluate separate instances of at fixed points. This takes the verifier additional time.

Matrix Multiplication Layers (counterexample)

Prerequisite: matrix multiplication layers page.

For matrix multiplication layers: consider , and consider the sumcheck relationship .

In matrix multiplication layers, the claim is always of the form , and the prover proceeds by first binding and before showing that . In the RLC claim aggregation case, we have claims Where and (otherwise they would be claims from the same "source" layer and would therefore be identical). The verifier samples random challenge . In this case, our sumcheck relationship is the following: Because and , there is no way to factor the above expression's RHS to combine terms in any way, and thus RLC claim aggregation is equivalent to not aggregating claims at all and simply running two separate sumchecks on

Input Layers (counterexample)

For input layers: RLC claim aggregation combines claims into a single claimed statement For public inputs, the verifier must evaluate each of and on their own, and thus nothing is gained by the combination.

For committed inputs, a polynomial commitment scheme may allow for cheaper evaluation proofs in the above form (vs. two separate evaluation proofs; one for each claim), but this is generally not the case.

Interpolative Claim Aggregation

Additional reading: See Tha13, page 15 ("reducing to verification of a single point"), for another description of the protocol, and Mod24, page 15 (Section 3.4, "Claim aggregation"), for a thorough description + optimization.

Interpolative claim aggreation works by having the prover and verifier both compute an interpolating polynomial , such that for the claims described earlier, i.e.

we have that

Note that the degree of is , as there are points for each of the coordinates which must be interpolated.

The prover then sends over the polynomial , i.e. the restriction of to points in generated by . Note that the degree of is , as is multilinear in each of its variables, and each of those variables is degree at most in the input variable for .

The verifier samples and sends it to the prover. The prover and verifier both compute , and the prover proves the single claim

where was sent by the prover and the verifier evaluates it at on its own.

Costs

The prover cost for interpolative claim aggregation is as follows:

- Given claims with variables each, is a -degree function in each of its components, and since is multilinear in each of its variables, is a univariate polynomial with degree . The prover must send evaluations to the verifier, although the first have already been sent implicitly in the form of the claims.

- The prover thus must evaluate at points. Each evaluation requires the prover to evaluate in time, and then in time. The prover's total runtime is thus .

The proof size for interpolative claim aggregation is as follows:

- As reasoned earlier in the prover cost section, the prover sends over evaluations of . The proof size is thus field elements.

The verifier runtime for interpolative claim aggregation is as follows:

- The verifier receives evaluations of from the prover and evaluates it at a random point . This takes time. Additionally, the verifier evaluates , which takes time as well. The verifier's total runtime is thus .

Optimizations

Remainder has a few built-in optimizations for interpolative claim aggregation which substantially lower the prover costs for claims with "structure" within their evaluation points. For more details, see Mod24, page 15 (Claim Aggregation section).

Matrix Multiplication Layer

A GKR "matrix multiplication" layer is one which takes as input two MLEs and outputs a single MLE whose evaluations are the flattened matrix multiplication of the evaluations of and .

Canonic matrix multiplication is defined as the following, given matrices resulting in :

where the above holds for , . We instead consider the multilinear extensions of the above matrices, such that

where . Then for all and we have

(Note that the above is also necessarily true for general , as multilinear extensions are uniquely defined by their evaluations over the boolean hypercube.) We wish to prove this relationship to the verifier using sumcheck. We can do this using Schwarz-Zippel against as follows: rather than checking the above relationship for all , the verifier can sample challenges and instead check the following relationship:

This is a sumcheck over just variables, and yields two claims (assume that is bound to during sumcheck) –

Costs

The prover cost for sumcheck over matrix multiplication is as follows:

- The prover must first compute the evaluations of and for . It already has the evaluations of and , and thus this preprocessing step takes .

- Next, the prover must compute sumcheck messages for the above relationship. The degree of each sumcheck message is , and thus the prover sends evaluations per round of sumcheck. Since we are sumchecking over , there are rounds of sumcheck and thus the prover cost is for the 'th round of sumcheck. The total prover sumcheck cost is thus

- The prover's total cost (preprocessing + sumcheck) is . Letting be a constant and allowing square matrices with , the prover's total cost is , which is asymptotically optimal for matrix multiplication.

The proof size for sumcheck over matrix multiplication is as follows:

- There are total sumcheck rounds, each with the prover sending over evaluations for a quadratic polynomial. The proof size is thus field elements, plus extra for the final claims on and .

The verifier cost for sumcheck over matrix multiplication is as follows:

- The verifier receives sumcheck messages with evaluations each, and each round it must evaluate those quadratic polynomials at a random point. Its runtime is thus with very small constants.

GKR Input Layer

We have now seen that a GKR interactive proof begins with the prover making a claim on the layered circuit's output layer and reducing this claim via sumcheck and claim aggregation to claims on layers closer to the circuit's input layer, e.g. .

At the end of this process, we should be left with only claims on input layer(s), e.g.

These claims are optionally aggregated via interpolative claim aggregation (note that RLC claim aggregation does not work for input layer claims; see here for more details) into a single claim

which the verifier must check on its own, optionally with help from the prover. There are several types of input layers, and we describe the methodology for each.

Public Inputs

Public input layers are circuit inputs where the prover sends the values to the verifier in the clear. In particular, this means that the verifier knows the full set of evaluations of over and can evaluate the MLE on its own. Thus:

- Before the prover generates the output layer claim challenges ( above), they send these evaluations to the verifier by absorbing them into the transcript.

- When the verifier is ready to check the claim , they use the aforementioned evaluations to directly evaluate at and check that the evaluation is indeed the claimed .

Committed Inputs

Committed input layers are circuit inputs where the prover sends a commitment to the values (generally as a polynomial commitment). Committed inputs are not directly revealed to the verifier (although they may leak information unless a zero-knowledge polynomial commitment scheme, like Hyrax, is used), and thus the prover must additionally help the verifier when they wish to check the input claim by providing an evaluation proof, which roughly shows that the polynomial which the prover committed to earlier actually evaluates to at the evaluation point .

(See KZG10, page 6, and Tha24, page 188 for more details). Let be the security parameter. Let be the MLE which the prover wishes to commit to. Let be the evaluation point, and let be the claimed value. Roughly speaking, a polynomial commitment scheme (PCS) consists of the following four functions:

- . here is the commitment key which the prover has access to while committing and generating evaluation proofs, and here is the verification key which the verifier has access to while checking an evaluation proof. This function takes in a single security parameter such that the resulting commitment scheme has roughly bits of soundness.

- . The function takes in an MLE (for our purposes; in general this can be a univariate or multivariate polynomial of higher degree) and generates a commitment to be sent to the verifier.

- . The function takes in an evaluation point and produces an evaluation proof that the original polynomial which was committed to in actually evaluates to . Note that the verifier uses to check the evaluation proof .

- . The function takes in a commitment and an MLE and outputs whether that MLE is the one committed to by , i.e. whether .

In addition to the above, a commitment scheme must satisfy hiding and evaluation binding.

- Hiding implies that given a commitment and fewer than evaluation pairs, an adversary cannot determine the evaluation for a point not in the set of evaluation pairs.

- Evaluation binding implies that given an evaluation point and a claimed value , a prover should be able to produce an accepting evaluation proof for generated with negligible probability.

In general, we run once and distribute the resulting to the prover and verifier, and focus on the and functions. During the interactive GKR protocol, the prover and verifier do the following:

- The prover invokes the functionality on and sends the resulting to the verifier. They send this value to the verifier before any claims on output layers (including challenges) are generated. Note that this takes the place of the prover sending the evaluations of in the public inputs section above.

- After the prover has sent all circuit inputs to the verifier in either committed or direct evaluation form, the verifier generates the output claim challenges and the prover and verifier engage in the GKR claim reduction protocols until we're left with a single claim .

- The prover then invokes the functionality on and the aforementioned values to produce evaluation proof , which the verifier receives and checks.

Remainder's GKR prover uses a non-ZK version of the PCS implicit in AHIV17 (also explicitly described in the GLS+21 paper as Shockwave), which we briefly detail in our documentation's Ligero PCS page. Remainder's Hyrax prover uses the ZK PCS explicitly described within WTS+17, which we briefly detail in our documentation's Hyrax PCS page.

"Fiat-Shamir" Inputs

A third type of circuit "input" is that of a "Fiat-Shamir" challenge value. These inputs are different from the others in the sense that the prover does not supply them at all, but rather the (interactive) verifier sends them after the prover has committed to all other input values. These values are used when the circuit itself is computing a function which requires a random challenge (see LogUp, e.g., for one usage of such challenges). In general, claims on these layers are checked via the following:

- First, as mentioned, the (interactive) prover sends all other inputs (both public and committed) to the verifier.

- Next, the verifier sends random values (we can view these as the evaluations of over ) to the prover as challenge values.

- When the verifier needs to check a claim on the Fiat-Shamir input layer, it can do so by simply referencing the evaluations it generated earlier to evaluate at and ensure that the evaluation is actually , exactly as is the case for public inputs.

Ligero Polynomial Commitment Scheme

References: GLS+21, page 46, AER24.

Prerequisites

As described within the committed input layers section, the Ligero polynomial commitment scheme (PCS) consists of a and an phase such that

- During , the prover sends a commitment for the input layer MLE .

- After running the rest of the GKR claim reduction process, we are left with a claim .

- During , the prover sends an evaluation proof showing that .

Short Introduction to Reed-Solomon Codes

We provide a brief introduction to Reed-Solomon codes, as these are prominently featured within the Ligero construction. First, we describe a few properties of general linear codes which will be useful:

- An -linear code is a subspace of dimension (i.e. is spanned by linearly independent basis vectors of length each) where implies that for all nonzero codewords .

- We define the Hamming weight is the number of nonzero entries in .

- For all distinct we have that , since the difference of two codewords is itself a codeword.

- The encoding step of a linear code can be described by a matrix-vector multiplication , where is the unencoded message and is the code's generator matrix. For simplicity we will just use as the encode function notation.